After some motivation from various researchers on Twitter: why don't we put studies we know won't be published on the internet somewhere..., I decided I would put my thesis up. Until I can re-analyze the new data I collected & actually attempt to have this thing published, of course. In the mean time, feel free to fill your mind and your time.

If you are lucky enough to have access, the full document can be found here or here.

ABSTRACT

Sexual

behavior and activity began to lose its sole purpose as sex for reproduction

early in the evolution of the genus Homo (Benagiano

et al., 2007). Consequently, humans have tried to utilize contraception ever

since they could document their existence. When used correctly, contraceptives

are enormously effective at preventing unintentional pregnancy. However, most

studies conducted on contraceptive behaviors have not been driven by theory.

The purpose of this research was to apply a theory to predict the contraceptive

use of females. Since life history theory is concerned predominantly with the

timing of reproduction, being that it is the final stage organisms can allocate

resources to in their lifetime (Griskevicius et al., 2011), life history theory

was applied for the current research. Participants (N = 283) completed surveys regarding their life history strategies

and contraception behaviors. Results revealed a two-factor solution that

represented r and K strategies. Multiple hierarchical regressions were utilized

to determine if the K and r strategy measures independently predict the

contraceptive measures as well as relevant life history outcomes. Although

lacking significance, results trended in the hypothesized direction. Results

did significantly predict a few relevant life history outcomes, including age,

delay of sex, sex frequency in the past year, religiosity, and current health.

Conclusions regarding future applications of this study’s measurement of

contraceptive effectiveness and the two-factor solution for measurement of life

history strategies are discussed.

Predicting Female Contraceptive Use: An Application of Life History Theory

Reproductive strategies of humans changed dramatically from

that employed by some of our common ancestors, for whom sexual activity was

restricted to sex for reproduction (Benagiano, Bastianelli, & Farris,

2007). Conceptive sex still remains as a valid reason for copulation; however,

non-conceptive copulations in primates are well documented. Bonobos (Pan paniscus), a species of chimpanzee, engage

in two distinct non-conceptive copulations: exchange sex, in which a female

acquires non-reproductive resources, and communication sex, sexual activity to

develop social relations or to reduce strain and aggression among group members

(deWaal, 1987). As illustrated by bonobos, sexual behaviors incorporate another

facet of sexuality that is considered typical

of sexuality in human beings: sexual behavior becomes something that can be

employed for reasons other than reproduction (Benagiano et al., 2007). These

findings suggest that sexual behavior and activity began to lose their sole

purpose as sex for reproduction early in the evolution of the genus Homo (Benagiano et al., 2007). Once “men

and women were able to separate with fairly high accuracy the ‘reproductive’

from the ‘non- conceptive’ aspects of reproduction, a real sexual revolution

took place” (Benagiano, Carrara, & Filippi, 2010, p. 97). This sexual

revolution occurred long before that of the 1960’s.

Contraception

Humans have tried to utilize contraception ever since they

could document their existence. Coitus interruptus,

withdrawal with ejaculation afterwards, was performed since ancient times. In

the 19th century, individuals started to monitor fluctuations in basal body

temperature and changes in cervical

mucus consistency to time ovulation;

implementation of these combined indicators was used for natural family

planning. In ancient Egypt and Rome, a device soaked with different extracts,

juices, lactic acid, or honey was placed in the vagina to prevent women from

conceiving; these recipes, noted in the Kahun Papyrusm, date as far back as

1850 BC. Three thousand years ago, dung from elephants or crocodiles was used

in India and Egypt to be introduced in the vagina prior to intercourse, acting

as an unsophisticated barrier and perhaps as spermicide. A physician was purported to have invented the condom between

1660-1685 for King Charles II, who was stricken with a large number of

illegitimate offspring. Since the 18th

century, condoms made of cloth or animal by-products including skin or

intestinal tissue were mass-produced. The 19th century brought

rubber condoms while the 20th century brought latex condoms (Li

& Lo, 2005).

The notion of placing a foreign object in the

uterus was first portrayed in fabled stories about African nomads who put tiny

stones into the uterus of their camels to prevent conception during lengthy

journeys. After ascertaining the anti-fertility effect of

intrauterine copper ions in rabbits, the first copper-T IUD was introduced in

1969. Exchanging the copper with progesterone

or levonorgesterol offered surplus non-contraceptive benefits, such as

decreasing pelvic infections (Li & Lo, 2005; Szarewski &

Guillebaud, 1991).

It was not until the turn of the 20th

century that we gained knowledge of reproductive endocrinology that would

eventually lead to applications in modern hormonal contraception. In the 1920s

administration of estrogen would render experimental animals infertile; in the

1930s both estrogen and progesterone caused anovulation. Through the hard work

of several renowned researchers in steroid chemistry, synthetic progesterone

and estrogen were produced (Szarewski

& Guillebaud, 1991). The first combined oral

contraceptive preparation, called Enovid was available in 1959, but the

estrogen dosage was high compared to pills used today (Szarewski &

Guillebaud, 1991).

The lower dose ethinyl-estradiol pills were available since 1961 and

even lower dose pills were in regular use since 1972 (Li & Lo,

2005).

Depo-Provera was the first injectable hormone developed and

it was approved for contraceptive purpose in the mid-1960s. Norplant was the

first contraceptive implant approved in 1984 as a multi-rod subdermal implant. A single-rod implant, Implanon, was launched in 1998. The

latest hormone delivery methods, specifically the transdermal patch,

Ortho-Evra, and the vaginal ring, NuvaRing, have been recently introduced as

different mechanisms of hormonal contraceptive transmission (Li & Lo,

2005).

Since

the earliest times, unusual ploys such as sneezing and vaginal douching with

diverse substances such as lemon juice or Coca-Cola have been used for

post-coital contraception. The modern hormonal method for emergency

contraception (EC) probably started in the 1920s when post-intercourse

administration of estrogen in animals prevented pregnancy; the first account of

EC use for humans was in the early 1960s, when high-dose diethylstilbestrol was

administered (Li &

Lo, 2005). Sterilization

for both men and women is also a very effective form of contraception and has

replaced the Pill as the most used method for women over thirty (Szarewski

& Guillebaud, 1991).

Contraceptive Facts

As of July 2012, 62 million women in the United States are

between the ages of 15-44: women who are sexually active and able to bear

children (Centers for Disease Control, 2009).

Individuals who did not apply a contraceptive method had an 85% chance

of becoming pregnant in the past year, intended or not (Trussell, 2011). One in

ten females are at risk for an unintended pregnancy, the highest proportion of

women being adolescents, between 15 and 19 year olds. Ninety-two percent of

women with at least a bachelor’s degree are currently using a contraceptive

method, compared to only 89% of females who do not have a high school diploma

(Mosher & Jones, 2010). Only 88% percent of women living below the

federal poverty line are using contraceptives, compared to 92% of women living

above the poverty line (Mosher & Jones, 2010).

Fifty-four percent of 2.9 million teenage women rely on the

pill as their primary method of contraception (Mosher & Jones, 2010). The

pill is one of the most effective methods, with an eight percent failure rate

with typical use (Trussell, 2011). When

used correctly, contraceptives are enormously effective at preventing

unintentional pregnancy. Females who use contraceptives consistently and

correctly account for only 5% of unplanned pregnancies (Gold, Sonfield,

Richards, & Frost, 2009). Using contraception consistently and correctly is

equated to having high contraceptive use skills. If an individual uses

contraception consistently and correctly, not only are they more skilled at

using the contraception, they are more skilled at preventing pregnancy. Several

hormonal methods, such as the pill, patch, vaginal ring, IUD, and implant

provide numerous health benefits beyond just preventing pregnancy. Prevention

of pregnancy is cited as the most common reason for using oral contraceptives

like the pill; however, over half of pill users also mention the additional

health benefits, including treatment for excessive menstrual bleeding, pain

associated with menstruation, or acne as reasons for use (Jones, 2011).

Less than 10% of women of reproductive age use a dual-method

(most often the condom in addition to another method; Eisenberg, Allsworth,

Zhao, & Peipert, 2012). Use of emergency contraception is a technique to

avoid pregnancy after unprotected intercourse or contraceptive failure

(Trussell & Raymond, 2011). Only one percent of women of reproductive age

have used emergency contraception. The age group with the highest possibility

for accidental pregnancy, females aged 18–29, are more apt than other aged

women to have used emergency contraception, which is considered a backup method (Frost, Henshaw, &

Sonfield, 2010). Again, emergency contraception is viewed as a method to use in

cases where other methods during or prior to intercourse were not

employed.

Knowledge about contraceptive methods is a robust predictor

of use. Of unmarried women aged 18–29, for every correct response on a

contraceptive knowledge scale, the likelihood of currently using a hormonal or

long-acting reversible method (i.e., the most effective methods) increased by

17%, and of using no method decreased by 17% (Frost, Lindberg, & Finer, 2012).

If an individual knows more about contraception, specifically the information regarding

effectiveness of each method, they are more likely to choose the most effective

method as their own method. Interestingly, 19% of women perceive they are

infertile, regardless of whether this belief is medically supported (Polis &

Zabin, 2012). This could explain the frequency of unplanned pregnancies within

this population if proper contraceptive methods are perceived as not needed and

thus not utilized.

Correlates of Contraceptive Use

Most studies conducted on contraceptive behaviors have not been

driven by theory. Previous studies have examined a multitude of factors correlated

with contraceptive behaviors. For example, one-third of women did not use

contraception because they believed they could not get pregnant at the time of

intercourse (Nettleman, Chung, Brewer, Ayoola, & Reed, 2007). If a woman doesn’t

think there was a risk of pregnancy during intercourse, she wouldn’t employ a

method. Another study revealed about 50% of coital events would be protected if

women expressed that they were committed to not becoming pregnant (Bartz, Shew,

Ofner, & Fortenberry, 2007). If a woman was explicitly devoted to

preventing pregnancy, she would be committed to protecting herself for at least

half of her coital events. Furthermore, if women reported that they communicate

with their sexual partners about contraceptive choices and issues infrequently,

they would be inconsistent contraceptive users (Davies et al., 2006). Also, increased

relationship quality was associated with decreased condom use (Sayegh,

Fortenberry, Shew, & Orr, 2006).

In addition, Asian, Latina, African American women and women

who were raised with a religion are less likely to use any contraceptive method

(Raine, Minnis, & Padian, 2003;

Kost, Singh, Vaughan, Trussell, & Bankole, 2008). Contraceptive failure

risk most severely affects the poorest females, women living below the 100%

poverty level (Kost et al., 2008). These women might have to rely on more

affordable, less effective methods, which are more likely to fail. Cultural

beliefs, values, and influences of the individual’s surrounding community can act

as barriers for the female to obtain contraceptives (Sable et al., 2000). Frequent discussions with friends about

contraceptives foster positive attitudes towards contraception and increased

satisfaction (Forrest & Frost, 1996).

Transportation often affects women’s abilities to obtain

contraception; women who had no insurance cite transportation difficulties as a

barrier more often than insured females (Sable, Libbus, & Chiu, 2000). If a

woman’s community isn’t as accepting of contraceptive behaviors, this might

stigmatize women attempting to prevent pregnancy; consequently, they might not

be able to obtain their preferred method. Method satisfaction is most likely in

women who acknowledge the pill’s non-contraceptive benefits, experienced few to

no side effects, and had used the pill previously (Rosenberg, Waugh, &

Burnhill, 1998). African Americans

report lower use of hormonal contraceptives and increased rates of sexually

transmitted infections, while Caucasians are less likely to use condoms for

intercourse (Buhi, Marhefka, & Hoban, 2010).

Likewise, African American students show an increased

incongruence in using effective methods of contraception compared to Caucasian

students (Gaydos, Neubert, Hogue, Kramer, & Yang, 2010). Abused women do

not use their preferred method compared to non-abused women (Williams, Larsen, &

McCloskey, 2008). Furthermore, research conducted on contraceptive behaviors

remains predominately located within the health fields (Skouby, 2010; Frost

& Darroch, 2008; Buhi, Marhekfa, & Hoban, 2010; Gaydos et al., 2010;

Ersek, Huber, Thompson, & Warren-Findlow, 2011).

It is somewhat apparent that predominately, the studies

conducted on contraceptive behaviors are not driven by theory. Upon further

examination of the variables correlated with contraceptive behaviors, one theory

that is a likely candidate for application in this area of research is life

history theory (LHT).

Life History Theory Literature

Charles Darwin proposed the theory of evolution by natural

selection over 150 years ago (Darwin, 1859). It has only been in the past 20

years that the psychological, social, and behavior sciences have integrated the

principles of evolution already deeply incorporated in biology and ecology. The

goal of evolutionary psychology is not only to incorporate evolutionary

biology, anthropology, neuroscience, and cognitive psychology to map human

nature, but also to rewrite existing literature, reframing previous efforts

into an evolutionary perspective (Tooby & Cosmides, 1992). It is worth

mentioning that evolutionary psychology is not to be acknowledged as a subset

of psychology, like social psychology or cognitive psychology, but rather as “a

way of thinking about psychology,” available as a lens for viewing any topic

therein (Cosmides & Tooby, 2000, p. 1). One evolutionary approach to the

study of individual differences is life history theory (LHT). Initially, biologists

and zoologists used life history theory to study species differences in

reproductive strategies (Promislow & Harvey, 1990, 1991).

Evolution is the outcome of a process in which

organisms compete to acquire resources from the environment to produce

offspring (Kaplan & Gangestad, 2004). Individual organisms “‘capture’

energy from the environment (through foraging, hunting, or cultivating) and

‘allocate’ it to reproduction and survival-enhancing activities” (Kaplan &

Gangestad, 2004, p.2). Selection will favor individual organisms that

efficiently capture resources and effectively allocate these resources to

increase fitness within their environment. Resources are not free; in reality,

individuals must live within fixed resource budgets, only spending what is

available. Allocation of a fixed budget necessitates trade-offs and

consequently, decisions must be made about the ways to spend this budget. Essentially,

LHT provides a framework addressing how individuals allocate resources to tasks

that maximize fitness in the presence of trade-offs. Allocations vary across

the lifespan and, consequently, LHT is concerned about the evolutionary forces

that shape the scheduling of events involved in growth, maintenance, and

reproduction (Kaplan & Gangestad, 2004).

Gadgil and Bossert (1970) established the first

modern LHT framework, hypothesizing tradeoffs as fixed resource budgets.

Organisms capture resources

from the environment, the rate at which they capture resources determines their

resource budget, and they can spend their resource budget on three distinctly

different behaviors: growth, maintenance, and reproduction. Through growth, individuals can increase

their resource capture rates for the future, thus maximizing future fertility;

organisms typically have an adolescent stage in which reproduction is not

possible and the primary resource allocation is on growth. Through maintenance, individuals repair

tissue and allocate resources to increase immune function. Through

reproduction, or reproductive effort,

individuals replicate their genes into offspring (Gadgil & Bossert, 1970).

Deciding whether to spend resources on current reproduction versus future reproduction is at the heart of the

somatic effort versus reproductive effort compromise. Somatic effort is

akin to investing in one’s self and reproductive effort is akin to spending

those investments that will allow for gene replication. Investment in somatic

effort is investing in future reproduction (Griskevicius, Delton, Robertson,

& Tybur, 2011). Individuals do not invest in themselves (somatic effort) as

an end in itself; rather, they invest for the sake of future reproduction. This

is exemplified in the individual that postpones reproduction immediately after

puberty, attends a university, acquires a degree, becomes employed where she or

he can accrue financial stability, and then finally decides to reproduce; with

the increased financial stability and higher education, this individual can

invest heavily in her or his offspring. Resources allocated to somatic effort, including the

growth and maintenance of body and mind and the accumulation of embodied

capital, cannot concurrently be allocated to reproductive effort, including sexual competition,

gestation, and birth (Griskevicius et al., 2011).

A second dilemma is the allocation of

resources to mating effort or parental effort (Figueredo et al., 2006). The procurement

and retaining of mating partners is described as mating effort; that is, the

time spent looking for potential mates and the time spent keeping these mates

around until reproduction is successful. Enhancement of survival of offspring

is described as parental effort; that is, the time spent feeding, nurturing,

educating, and protecting offspring until they reach maturity. However, a

trade-off also exists between these two efforts. For example, effort spent

parenting cannot be spent acquiring new mates.

Within parental effort lies yet another

trade-off: offspring quality versus quantity. This fundamental trade off

assumes that resources are limited so as investment in one offspring increases,

investment in each other individual offspring decreases; increased investment

in offspring enhances the offspring’s reproductive success; and maternal

fitness is calculated by the quantity of offspring that reach maturity and

their ensuing lifetime reproductive success (Gillespie, Russell, & Lumma,

2008). Therein lies an evolved trade off for females between offspring quality

versus quantity (Lack, 1947). Although, in comparison to other species, humans

tend to favor quality over quantity in offspring, there are still individual

differences in this reproductive decision. Increased maternal embodied capital

increases child survival (Lawson et al., 2012). Birth, difficult and painful in

humans, is risky for both the fetus and the mother (Mace, 2000). Although risks

for maternal mortality are high and vary by region, risks to the baby are still

greater. The earlier a child is weaned, the greater the risk of infant

mortality (Mace, 2000); cessation of weaning is most likely due to impending

pregnancy. Again, the quality of offspring is threatened when quantity of

offspring increases. Offspring competition for resources is also a source of

risk and mortality; larger quantities of siblings competing for food leads to

decreased height in adolescence, further diminishing their future reproductive

success (Lawson et al., 2012).

Life

History strategies. How and when an individual decides to reconcile these resource

allocation trade-offs comprises that individual’s LH strategy (Griskevicius et

al., 2011; Gadgil & Bossert, 1970). Several environmental features influence LH

strategies; factors include harshness (e.g., the age and sex-specific rates of mortality),

unpredictability (e.g., the uniformity of harshness from one time to another),

and resource scarcity (e.g., the obtainability of resources and level of

competition for resources; Ellis et al., 2009). Species that

evolved in harsh, unpredictable, resource scarce environments are inclined to

implement distinctive LH strategies (Griskevicius et al., 2011). For example, a

species that evolved in a harsh and unpredictable environment will invest less

in somatic effort, reach sexual maturity quickly, and start reproducing at a

high rate; this fast strategy or r strategy is adaptive for members of such

species since reproducing quickly mitigates the risk of death without leaving

behind any offspring. These individuals invest in reproductive effort at the

cost of somatic effort. In contrast, investment in somatic effort heightens an

individual’s capacity to compete for mates and invest in offspring; a species

that evolved in a predictable environment follows a slower strategy or K

strategy, investing more in somatic effort and delaying reproduction

(Griskevicius et al., 2011). These individuals invest in somatic effort at the

cost of investment in current reproduction effort, opting for future

reproductive effort.

LHT can be exemplified by comparing the strategies

displayed by r-selected species, the fast individuals, which invest heavily in

reproduction with short life spans, with K-selected species, the slow

individuals, which invest heavily in their own development and that of their

offspring. Fast, r-selected species

evolved in unstable, harsh, and unpredictable environmental conditions, leading

to a strategy focused on producing high offspring quantity. Rabbits demonstrate

quick sexual development, low parental investment, short life expectancy, and high

competition for resources because they evolved in environments where short-term

strategies increased fitness.

Conversely, K-selected species evolved under stable and predictable

conditions, leading to a strategy focused on survival of high offspring

quality. Elephants demonstrate slow sexual development, high parental

investment, long life expectancy, and low competition for resources because

they evolved in stable environments where long-term strategies increased

fitness (Figueredo, Vasquez, Brumbach, & Schneider, 2004).

Humans are characteristically defined by the

substantial investments they make in somatic development at the cost of early

reproduction. Compared with chimpanzees, humans reach physical maturity much

later and reproduce at an even later age (Kaplan, Hill, Lancaster, &

Hurtado, 2000). Originally, comparative biologists concentrated on describing

LH strategies typical of a certain species, and then comparing the strategy of

that species with the strategy of another (Lack, 1950); accumulated evidence,

however, indicated adaptive within-species variation in LH strategies exist in

many taxa (Daan & Tinbergen, 1997; Tinbergen & Both, 1999). Organisms appear to implicitly monitor

current and expected states of their environments, regulating the LH strategies

they engage (Ellis et al., 2009). Instead of exhibiting a fixed strategy for

life, LH strategies show environmental exigency in reply to precise cues during

childhood and adulthood. According to LHT, the environmental factors linked to

different LH strategies in modern human environments are cues such as the local

mortality rate and the availability of resources in the local environment

(Kaplan & Gangestad, 2005; Quinlan, 2007; Worthman & Kuzara, 2005).

LHT suggests that since an individual’s resources are

limited, the individual must choose

between r and K strategies; the individual must choose to invest in their offspring or not, put off mating or not,

and have few or many offspring (Kruger & Nesse, 2004, 2006). According to

LHT, a continuum for humans exists from a slower course, high K, to a faster

course, low K (Bielby et al., 2007; Ellis et al.,

2009). An unpredictable and harsh environment, low investment from

mother and father when growing up, father absence, stepfather presence, low

social support, and high mortality risk are factors that contribute to the

manifestation of a low K strategy, similar to the r strategy of other species

(Figuredo et al., 2006). A predictable environment, high mother and father

nurturing while growing up, high social support, and low mortality risk are

factors that could contribute to the manifestation of a high K strategy

(Figueredo et al., 2006). These choices in strategy manifest in behaviors existing

within two clusters; mating strategies form a continuum, with most individuals

falling somewhere along this range (Figueredo et al.,

2004). The high K strategy involves clusters of behaviors such as

delayed puberty, slow sexual maturation, selective mating, sexual restraint,

extensive parental investment, consideration of risks, long lifespan, increased

inclusive fitness, extensive somatic investment, high cooperation, high

altruistic behaviors, monogamy, long term thinking, and intensive offspring

investment. The low K strategy involves clusters of behaviors such as preference

for sexual variety, sexual promiscuity, unrestrained sexuality, risk taking,

aggression, early puberty, quick sexual maturation, impulsivity, low romantic

attachment, low cooperation, rare altruistic behaviors, disregard of social

rules, manipulative, exploitative, short term thinking, and increased fecundity

(Figueredo et al., 2006).

The assumption, however, that an individual’s

resources are limited, forcing them to choose between traditional r and traditional

K strategies has been challenged. Rowe, Vazsonyi, and Figueredo (1997) state: “…it

may be possible for an unusually resource rich male to pursue a mixed strategy

combining certain elements of both” (p.106). It is reasonable to think that

individuals with limited resources are forced to choose between r and K

strategies, but individuals that have plentiful resources might be able to

exhibit traditional r and traditional K strategies. An individual with increased health, energy,

and wealth might be able to exhibit both traditional r and K strategy specific

behaviors simultaneously.

It is proposed that the traditional view of the K strategy

be maintained with respect to future time perspective, long-term mating

strategy, and environmental input. Concurrently, sexual drive, sexual desire, sexual

flexibility, and lack of sexual restraint (Figueredo et al., 2006) should be

removed from K and placed on a separate factor; this second factor could be

described as r. Figueredo and others (2006) include sexual restraint as

dimension of the K Factor: high K individuals are more likely to delay sexual

activity and engage in less risky sexual behaviors. Indicators of sexual

restrictedness include increased religiosity, endorsing value and health

reasons for abstaining from sex, perceived abilities to refuse sex, sexual

decision making skills, positive endorsement of teenage abstinence, acceptance

of norms prohibiting sex before marriage, intentions to abstain, and pro-social

behaviors (Figueredo et al., 2006; Brumbach, Walsh, & Figueredo, 2007). According

to this traditional view, high K individuals will experience sexual feelings

and attractions later than low K individuals; concurrently, low K individuals

will be more impulsive, sociable, risk-taking, and emotional in sexual

relationships compared to their high K counterparts (Figueredo et al., 2006). However,

this traditional view does not account for individuals that exhibit high K

strategies in non-sexual clusters of behavior while exhibiting traditional low

K strategies in sexual clusters of behavior. Individuals that show low “sexual

restraint,” such as engaging in intercourse at a younger age and more

frequently, can simultaneously engage in high K behaviors, such as attending a

university with long term career goals.

Life history theory is concerned predominantly with the

timing of reproduction, since that is the final stage organisms can allocate

resources to in their lifetime (Griskevicius et al., 2011). The question of how

individuals time their reproduction can be answered: they use contraception.

For example, many insist prior to the sexual revolution of the 1960’s that the

female’s only way of preventing pregnancy was by acting as a gatekeeper: to say

no to any unworthy mate; this however does not seem to make sense (see also

Ryan & Jethá,

2010; Pillard, 2007; Hayes & Carpenter, 2010; Wiederman, 2005; Schick,

Zucker, & Bay-Cheng, 2008). Humans have known the benefits of

non-conceptive sex since the beginning of the genus Homo (Benagiano et al., 2007; 2010). Our animal kingdom relatives

have also found ways to employ contraception in order to prevent pregnancy,

seen in wooly spider monkeys (Glander, 1994; Strier, 1993; Strier &

Ziegler, 1994), red colobus monkeys (Wasserman et al., 2012), and even

elephants (Shuker, 2001). Furthermore,

the history of contraception, contraceptive practices, and the extensive amount

of information collected on how to prevent pregnancy supports the notion that

women did not have to serve as gatekeepers (Meena & Rao, 2010; Li & Lo,

2005).

If women wanted to time their reproduction they would go to

great lengths to prevent pregnancy. Also, it does not seem logical for an early

human female to insert one of many of the previously mentioned substances into

her vagina (Li & Lo, 2005), a rather dangerous and sometimes deadly task,

just to keep her mate happy; her drive for sex must have been just as strong.

As previous literature has indicated, a traditionally high K woman that wished

to maintain her desires for future reproduction would have the only option of abstinence

(Buss & Schmitt, 1993). Humans however, are highly sexual; this is even

more apparent when researching all the methods of contraception that have ever

been invented and utilized.

In this light, a low sexually restrained woman isn’t forced

to life the life of a low K female: she can engage in high-K nonsexual clusters

of behavior and “low K” sexual clusters of behavior simultaneously. To that

end, a second factor must be examined. This new factor, r, is sexual clusters

of behavior. Humans have non-sexual clusters of behavior and sexual clusters of

behavior. Those sexual clusters of behavior are sex drive, attitudes towards

sex, sexual excitability, and sexual sensation seeking; those behaviors also

lie on a continuum. Individuals can be low in sexual restraint (r) or high,

just as much as they can be high or low on the K spectrum. With contraception,

individuals that engage in high r behaviors, such as engaging in intercourse at

a younger age and more frequently, can simultaneously engage in high K

behaviors, such as attending a university with long term career goals because

intercourse does not lead to reproduction.

Concluding, to

measure life history strategy on one continuum, with sexual and non-sexual

clusters of behavior within the single continuum, does not reveal the whole

picture of human life. Specifically, high K, high r individuals are being

missed. It is through the use of contraceptives females can pursue a mixed

strategy of combining both r and K strategies. Although women have been

practicing contraception since they could keep written records, it was only

recently that highly effective hormonal methods allowed women to almost perfect

their contracepting behaviors (Szarewski & Guillebaud, 1991). Since sex

with contraception lowers the risk of pregnancy, women can combine r and K

strategies. High K specific strategies such as high personal investment

(attending a university, pursuing a career, etc.), delay of reproduction, and

increased investment in offspring quality with birth spacing can be achieved by

utilizing an effective form of contraception. However, these women can also

engage in a high frequency of intercourse both inside and outside the context

of relationships, a strategy often displayed by high r individuals. On the

contrary, individuals that are seen as traditionally high K, possessing high

sexual restraint, would thus exhibit low r clusters of behavior: sex only for

reproduction and selective, restricted long-term mating (see Table 1).

Table 1

Hypothesized

results for contraceptive effectiveness

Strategy

|

High

K

|

Low

K

|

Low

r

|

Sex only for reproduction,

high sexual restraint, committed and not active. Selective, restricted long

term mating.

Method: very

effective birth control and highly skilled use (Purposeful Abstinence).

|

Non-normal population, not interested in sex, high sexual

restraint, and potential floor effect. Varied, unrestricted short term

mating.

Method: no

contraceptive method used since not engaging in sexual intercourse (Indifferent Abstinence).

|

High

r

|

Frequent sex for non-reproduction, low sexual restraint,

committed and very active. Selective, restricted long term mating.

Method: very

effective birth control and highly skilled use (pill, IUD, implant, shot,

etc.)

|

Frequent sex for non-reproduction, low sexual restraint,

promiscuous and very active. Varied, unrestricted short term mating.

Method: no

method, least effective method and low skilled use (withdrawal, fertility

awareness, etc.)

|

Contraception makes it possible for an individual to begin

sexual activity at an early age while investing in self-development (e.g.,

pursuing a college degree), to have sex with multiple partners without

conception, choose one long-term partner (with or without non-conception extra

pair copulation), and invest heavily in a limited number of children (due to

contraception’s child spacing and limiting benefits). Through contraception, females can pursue

promiscuous or committed sex; females can have as much sex without conception

as desired; and consequently, enjoy sex proximately without the ultimate

consequence of pregnancy.

Hypotheses

The purpose of this research is to

investigate the relationships between r and K strategies and the use of

contraception. Specifically, the

following hypotheses will be tested:

1.

An interaction between r

and K strategies will be found to predict method effectiveness, such that high r and high K women will

utilize the most effective methods.

2.

An interaction between r

and K strategies will be found to predict contraceptive knowledge, such that high r and high K women

will be most knowledgeable about contraception.

3.

An interaction between r

and K strategies will be found to predict general attitudes towards contraceptives, such

that high r, high K women will have the most positive attitudes.

4.

An interaction between r

and K strategies will be found to predict morality attitudes towards contraceptives, such

that high r, high K women will be the most morally accepting of contraceptives.

5.

An interaction between r

and K strategies will be found to predict contraceptive self-efficacy, such that high r,

high K women will have the highest contraceptive self-efficacy

Method

Participants

Two hundred and eighty-three women participated in the

study. Participants were either recruited using the SONA system within the

Western Illinois University (WIU) Psychology Department or through convenience

sampling, using the software survey data collection tool SurveyMonkey

(SurveyMonkey, Inc.).

The mean age of total participants was 23.75 (SD = 7.35), and 82.7% of the sample was

Caucasian, 8.8% African American/African, 1.8% Asian American/Asian, 2.8%

Hispanic, and 2.8% Multiple Ethnicity/Mixed. Of the participants, 42.8% were

single and dating exclusively, 17.3% were single and not dating, 13.4% were

married, 12.0% were single and dating casually, 8.1% were engaged to be

married, and 5.3% were single and cohabiting. The majority of participants identified

as heterosexual (90.1%), 6.4% identified as bisexual, and 1.4% identified as

homosexual. Of the participants, 26.9% identified as Catholic, 26.9% identified

as Christian, 19.1% identified as having no religious affiliation, 9.2%

identified as Atheist, and 3.5% identified as Agnostic. The majority of participants

were insured by their parents (54.1%), 15.2% of the participants were insured

by their employers, 9.5% of the participants were insured by their university,

5.3% of the participants were insured by the government, and 5.3% of the participants

were uninsured. Lastly, 84.1% of participants identified their most recent sex

partner as being male and 2.5% identified their most recent sex partner as

female. For the highest education level of participants, 17% were Freshman,

22.1% were Sophomore, 18% were Junior, 7% were Senior, 12% were Graduate

Student, 14% graduated college, 6% held a professional degree, 4% completed

graduate school, 5% received a high school education or less.

Contraceptive method.

Two hundred and

seventy-six participants reported a primary method, or their primary method was

determined by their responses on Current Contraceptive Method and Recent

Contraceptive Method questions of the CMQ. The majority of participants

reported the pill as their primary contraceptive method (35. 8%), 23% reported

using no method, 21.2% reported using the condom as their primary method, 6.9%

reported using the IUD as their primary method, and 3.3% reported using the

vaginal ring as their primary method.

Participants could denote any

methods they use, including more than one method. For both Current and Recent

Methods reported on the CMQ, 11.4% of participants indicated they used no

method, 27.3% of participants indicated they used the pill, 28.9% indicated

they used the condom, 14.0% indicated they used withdrawal, .05% indicated they

used fertility awareness, .04% indicated they used the IUD, .03% indicated they

used the ring, .02% indicated they used the shot, .01% indicated they used the

patch, .01% indicated they use the implant, .008% indicated they use male

partner sterilization, .006% indicated they use the female condom, .004%

indicated they used spermicide, and .002% indicated they used female

sterilization.

Participants could also denote if

they were dual method users (e.g., pill and condom, vaginal ring and condom,

etc.); participants must have reported using the condom in addition to another

method. Dual method use was inferred from their responses on the Current or

Recent Methods portion of the Contraceptive Methods Questionnaire as well as

their responses on the two dual method intention items on the General Errors in

Contraceptive Use Scale. The majority of participants were single method users

(N = 208), while 68 participants reported being dual method users.

Interestingly, many participants reported using the withdrawal method in

addition to other methods listed in the Current or Recent Methods on the CMQ. While

majority of participants did not denote using the withdrawal method in addition

to another method, 68 participants reported using withdrawal in conjunction

with other methods.

Analysis participants.

Participants

recruited outside of the WIU Department of Psychology’s Human Subject Pool only

made up 12.6% of participants used in analysis. The mean age for participants

in analysis was 21.56 (SD = 5.13). Of

analysis participants, 70.5% were Caucasian, 22.1% were African

American/African, 3.2% were Hispanic, and 4.2% were Multiple Ethnicity/Mixed.

Of analysis participants, 28.4% were college freshman, 20.0% were college

sophomores, 17.9% were college juniors, 17.9% were college seniors, 6.3% were

graduate students, 3.2% completed graduate school, 1.1% graduated from college,

and 2.1% held a professional degree. Of analysis participants, 21.1% were not

dating, 11.6% were dating casually, 50.5% were dating exclusively, 8.4% were

engaged, and 8.4% were married. Of analysis participants, 94.7% were

heterosexual, 1.1% were homosexual, and 4.2% were bisexual. Of analysis

participants, 13.7% reported no religious affiliation, 2.1% identified as

Atheist, 1.1% identified as Agnostic, 27.4% identified as Catholic, and 37.9%

identified as Christian. The Institutional Review Board of WIU reviewed and

approved this study before administration.

Procedure

Participants read an Informed Consent before any data was

collected; further participation signified informed consent. Time of completion

ranged between 45 minutes to one hour. The measures administered through the

SONA system and through SurveyMonkey were identical, with the exception that

SurveyMonkey allowed a skip question formation for ease of survey completion. In

addition, titles of measures were not included as to avoid any priming effects

of the scale title. Participants were given a debriefing form that reminded

them of the continued privacy of their responses and described the purpose of

the study. Eligible WIU participants were awarded PURE credit, a requirement

for the completion of General Education Psychology courses, upon completion of

the study.

Measures

Demographics. A demographic questionnaire was created to gather demographic

information from the participant. Items include age, year in school, ethnicity,

religion, religiosity, current relationship status, present sexual orientation,

current living arrangements, health insurance provider, current health, sexual

status, intercourse frequency in the past year, age at first intercourse,

number of children, frequency of miscarriages, frequency of abortions, gender

of the most recent sexual partner, sterilization, and infertility (see Appendix

A).

Contraceptive

Methods Questionnaire. The

Contraceptive Methods Questionnaire consists of a checklist for known methods

of contraception (see Appendix B). The questionnaire addresses contraceptive

methods (i.e., birth control pills, condoms, vaginal ring, etc.) participants

are currently using and used during their most recent intercourse. The

questionnaire includes a list of possible known methods of contraception as

well as the informal terms, often a brand name (e.g., The Pill, Depo-Provera,

NuvaRing, etc.).

Contraceptive Use

Questionnaire.

The Contraceptive Use Questionnaire (CUQ) consists of six subscales: General

Knowledge of Contraception Scale; General Errors in Contraceptive Use Scale;

Intention, Consistency, and Perfection of Contraceptive Use Scale; and Method

Specific Errors in Contraceptive Use Scale. The CUQ was created through

modification of the Contraceptive Utilities, Intentions, and Knowledge Scale (CUIKS; Condelli, 1984). The CUIKS addresses the contraceptive

behaviors of the participants, including how “well” they use their method. The

scale was modified for the current study’s specific needs.

General Knowledge of Contraception Scale. The General Knowledge of

Contraception portion was modified from the CUIKS for brevity and to include

more relevant forms of contraception used today (see Appendix C). Cronbach’s

alpha revealed satisfactory reliability (α = .86). The section consists of

21 multiple-choice questions assessing general knowledge regarding

contraception. A sample knowledge item is: “The pill: (a) prevents ovulation,

(b) keeps cervical mucous very thin, (c) changes the lining of the uterus to

make implantation unlikely, (d) both A & C, (e) all of the above;” the

correct answer being A. The General Knowledge of

Contraception Scale has a total score of 21 points, with each correct answer

earning the participant one point and each incorrect/no response earning the

participant zero points. Higher scores on the General Knowledge Scale indicate

greater knowledge of contraception. Two hundred and forty seven participants

completed the General Knowledge of Contraception Scale; the mean score was

12.40 (SD = 2.66).

General Errors in Contraceptive Use Scale. Participants

completed the General Errors in Contraceptive Use Scale that assessed their

contraceptive use behaviors (see

Appendix D). A sample item is: “I have engaged

in unprotected sex because the event was unplanned or undesired;” participants

responded to seven items on a five-point Likert scale from 1 (definitely not true of me) to 5 (definitely true of me). Total scores were

calculated by reversing four items then summing over items; higher scores

indicate greater general contraceptive use skill. Cronbach’s alpha was low for

this scale (α =

.68), which could be attributed to two of the items specifically assessing

dual use behaviors, while four specifically assessed their engagement in

unprotected intercourse. Two hundred

and thirty-seven participants completed the General Skills in Contraceptive Use

Scale; the mean score was 23.06 (SD =

5.13).

Intention, Consistency, and Perfection of Contraceptive Use Scale.

The

Intention, Consistency, and Perfection of Contraceptive Use Scale (ICPCUS)

consists of items specific to different forms of contraception that measure

intention to use, consistency in use, and perfection in use for the pill, the

condom, the IUD, the vaginal ring, or other methods (see Appendix E). For each

method, two items measured intention, two items measured consistency, and two

items measured perfection. For example,

for the Pill, an intention item is: “I will use the pill during my next sexual

intercourse.” A consistency item is: “I

would describe my pill contraceptive behavior in the past 3 months as

consistent (administering the pill daily at the same time, etc.).” A perfection item is: “I would describe my

pill contraceptive behavior in the past 3 months as perfect (administering the

pill daily at the same time, etc.).” Responses were made on a five-point scale

from 1 (definitely not true of me) to

5 (definitely true of me);

participants were marked N/A (not

applicable) for methods they were not employing. For participants’ primary

method, the scores were summed for each area and higher scores indicate greater

intention, consistency of use, and perfection of use by the participant,

comprising their Primary Method General Use Skills score. Two hundred and

seventy-five participants completed the Intention, Consistency, and Perfection

of Contraceptive Use Scale; the mean score was 17.88 (SD = 11.95).

Method Specific Errors in Contraceptive Use Scale. Participants completed a Method

Specific Errors in Contraceptive Use Scale that assessed method specific

contraceptive use behaviors (see Appendix F). Eleven items measured

method-specific errors; participants answered questions specific to the pill (2

items), the condom (6 items), the IUD (1 item), the vaginal ring (2 items), and

answered not applicable (N/A) for

methods they were not using. A sample item is: “During the past year, I took my

pill at the same time every day;” participants responded to the 11 items using

a five-point Likert scale from 1 (definitely

not true of me) to 5 (definitely true

of me), and participants not using that specific method reported not

applicable. For the participants’ primary method, after reverse scoring, scores

were averaged; higher scores indicate greater method specific use skill,

comprising their Primary Method Specific Use Skill score. Two hundred and

seventy-four participants completed the Method Specific Errors in Contraceptive

Use Scale; the mean was 4.93 (SD =

6.60).

Sociosexual

Orientation Scale.

The Sociosexual Orientation Scale (SOI; Simpson & Gangestad, 1991) measured

differences in willingness for or endorsement of casual, promiscuous sex (see Appendix

G). The seven-item scale has two past behavioral items and one future

behavioral item; one item assesses fantasies with participants responding on an

eight-point Likert from 1 (never) to

8 (at

least once a day). Three items assess attitudes, with participants

responding on a nine-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 9 (strongly

agree). The weighted total was computed using scoring from Simpson and

Gangestad (1991); of the 139 participants that completed the SOI, the mean was

43.97 (SD = 30.52). Higher scores represent an unrestricted sociosexual orientation.

Cronbach’s alpha (.77) demonstrated the internal consistency of the scale.

Brief Sexual

Attitudes Scale. The

Brief Sexual Attitudes Scale (BSAS; Hendrick, Hendrick, & Reich, 2006) assessed

sexual attitudes (see Appendix H). The overall Cronbach’s alpha for the BSAS

was .83, (N = 140). The BSAS has four subscales consisting of Permissiveness (10 items; α

= .90) with a mean of 2.16 (SD

= .90), Birth Control (3 items; α

= .86) with a mean of 4.56 (SD =

.73), Communion (5 items; α = .80)

with a mean of 3.87 (SD = .85), and Instrumentality (5 items; α

= .75) with a mean of 3.01 (SD = .84). A sample item from the

Instrumentality subscale is: “The main purpose of sex is to enjoy yourself;” 140

participants responded on a five-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree with the statement) to

5 (strongly agree with the statement).

Sexual Desire

Inventory. The

Sexual Desire Inventory (SDI; Spector, Carey, & Steinberg, 1996) assessed sexual

desire (see Appendix I). The SDI is a 14-item scale that includes two subscales:

Dyadic Sexual Desire (8 items; α = .90), which measures the desire to engage in sexual

behaviors with another individual, and Solitary Sexual Desire (6 items; α = .91),

which measures the desire to engage in sexual behaviors in solitary. A sample

Solitary Sexual Desire item is: “Compared to other people of your age and sex,

how would you rate your desire to behave sexually with a partner?” and 139 participants

responded on a 9-point Likert scale from 0 (much

less desire) to 8 (much more desire).

Higher scores are indicative of higher sexual desire; the mean for SDI Dyadic

Sexual Desire was 4.75 (SD = 1.67)

and the mean for SDI Solitary Sexual Desire was 2.37 (SD = 2.04).

Sexual Sensation

Seeking Scale. The

Sexual Sensation Seeking Scale (Kalichman et al., 1994) assessed the need for

varied, novel, and complex sexual experience and risk-taking behaviors to

enhance the sexual experience (see Appendix J). The ten-item scale has a

Cronbach’s alpha of .83. A sample item is: “I enjoy watching ‘X-rated’ videos;”

138 participants responded on a four point Likert scale from 1 (not at all like me) to 4 (very much like me). Higher scores were

indicative of higher sexual sensation seeking; the mean was 2.13 (SD = .58).

High-K Strategy

Scale. The

High-K Strategy Scale assessed the life history strategy of individuals

(Giosan, 2006; see Appendix K). The 26-item scale tapped into health,

attractiveness, social capital, and upward mobility; the scale is scored in the

slow strategy direction. The scale had a high internal consistency reliability,

α = .96. A

sample item is: “I live in a community to which I am well suited;” participants

responded on a five point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly

agree). Of the 222 participants that completed the scale, the mean

score was 5.03 (SD = 1.08).

Mini-K. In the context of life history

theory, Figueredo and associates developed the Mini-K in 2006 (see Appendix L).

The Mini-K is a 20-item scale that measured the extent to which participants

endorse slow life history strategies. The Cronbach’s alpha of the scale was

moderate, α = 83. A sample item is: “I am often in

social contact with my blood relatives.” One hundred and thirty nine participants

responded to the items on a seven point Likert scale from 1 (disagree strongly) to 7 (agree strongly). The mean for the Mini-K

was 5.41 (SD = .67).

Contraceptive

Attitudes Scale. The Contraceptive Attitudes Scale measured

attitudes towards the use of contraceptives in general (Black & Pollack,

1987; see Appendix M). The scale consists of 17 positive items and 15 negative

items; sample items from the scale include: “It is no trouble to use

contraceptives” and “I believe it is wrong to use contraceptives.” Two hundred

and twenty two participants responded on a five-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree)

to 5 (strongly agree). Higher scores indicate more positive

attitudes towards using contraceptives after reverse scoring; the mean was 3.27

(SD = 1.54). The scale’s internal

consistency reliability was high (α = .93).

Contraceptive

Immorality Scale. The

questions pertaining to contraceptive immorality were adapted from A Scale to

Assess University Women’s Attitudes About Contraceptives (Fisher et al., 1998; see Appendix N). Only five

items are utilized from this measure to ensure brevity. A sample item is:

“Using contraception is immoral;” 169 participants responded on a five-point

Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly

agree). All 5 items were reverse

scored; higher scores indicated higher belief that contraception is moral.

Internal consistency reliability was high α =.88, (M = 4.67, SD = .61).

Contraceptive

Self-Efficacy Scale. The

Contraceptive Self-Efficacy Scale (CSE) assessed motivational barriers to

contraceptive use among sexually active adolescent women (see Appendix O).

Levinson (1986) created the scale to measure the ability of a female adolescent

to control sexual and contraceptive situations. Cronbach’s alpha for this measure

was adequate, (α

=.64). A sample item is: “When I have sex, I can enjoy it as

something that I really wanted to do;” 214 participants responded on a

five-point Likert scale from 1 (not at

all true of me) to 5 (completely true of me). The mean for the

CSE was 3.96 (SD = .55).

Hurlbert Index of

Sexual Excitability. The Hurlbert Index of Sexual Excitability

(HISE; Apt & Hurlbert, 1993) assessed a female’s ability to become sexually

excited (see Appendix P). The scale consists of 25 items and participants responded

on a five-point Likert scale from 0 (never)

to 4 (all of the time). A sample item

is: “I find sex with my partner to be exciting.” Higher scores indicate higher

sexual excitability (M = 3.90, SD = .63). Two hundred and ten participants

completed the HISE and Cronbach’s alpha for this measure was high, (α =.90).

Consideration of

Future Consequences Scale. The

Consideration of Future Consequences Scale (Strathman, Gleicher, Boninger, &

Edwards, 1994) assessed an individual’s consideration of distant outcomes of

current behaviors and the extent of the influence of these outcomes (see

Appendix Q). Only the Future Orientation subscale was used for the purpose of

this study. The Future Orientation subscale has a mediocre Cronbach’s alpha of

.64. The subscale has five items; a sample item from the Future Orientation subscale

is: “I consider how things might be in the future and

try to influence those things with my day-to-day behavior.” One hundred and

thirty-nine participants responded on a five-point Likert scale from 1 (extremely uncharacteristic) to 5 (extremely characteristic). Higher scores

on the subscale indicate greater consideration of future consequences (M = 3.79, SD = .57).

Data Screening

The data were checked for univariate

outliers by examining box plots. Two participants were noted as being outliers

on three or more scales and removed from analysis; likewise, individuals that

self-reported as being abstinent were removed from analysis (N = 10). The minimum amount of data

needed for subsequent factor analyses were marginally satisfied, with a final

sample size of 96 (using listwise deletion). The skewness and kurtosis for each

scale were within the tolerable range for assuming a normal distribution and

examination of the histograms and stem-and-leaf plots revealed the

distributions to look normal.

Life History Strategies Factor Analysis

First, the Brief Sexual

Attitudes Scale was divided into the four subscales (Permissiveness, Communion,

Birth Control, and Instrumentality), the Sexual Desire Inventory was divided

into the two subscales (Solitary and Dyadic), and only the Future Orientation

subscale was used from the Consideration of Future Consequences. The HKSS,

Mini-K, Sexual Sensation Seeking Scale, Hurlbert Scale of Sexual Excitability,

and Sociosexuality Inventory, and the aforementioned subscales were utilized in

the factor analysis. See Table 2 for summary of scales used in the Life History

strategies factor analysis. Second, the factorability of the 12 scales was

examined. The factorability of the 12 scales was assessed using the

Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy, which was above the

recommended value of .6 (.62), and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was

significant, χ2

(66) = 231.98, p < .01. The

diagonals of the anti-image correlation matrix were all over .5 (with the

exception of Brief Sexual Attitudes Birth Control, at .42), supporting the

inclusion of each item in the following factor analysis. Brief Sexual Attitudes

Birth Control and Brief Sexual Attitudes Instrumentality had initial

communalities below .2 (see Table 3). Sexual Desire Inventory Dyadic, Brief

Sexual Attitudes Communion, and Future Orientation had initial communalities

below .3 (see Table 3). HKSS, Mini K, Brief Sexual Attitudes Permissiveness,

Sexual Desire Inventory Soloitary, Sexual Sensation Seeking, Hurlbert Scale of

Sexual Excitability, and Sociosexuality had initial communalities above .3 (see

Table 3).

Table 2

Descriptive Statistics Summary

for Life History Strategies Scales

Scale

|

N

|

# of

Items

|

Mean

|

SD

|

α

|

Sociosexuality Inventory

|

139

|

7

|

43.97

|

30.52

|

.77

|

Brief Sexual Attitudes Permissiveness

|

140

|

10

|

2.16

|

.90

|

.90

|

Brief Sexual Attitudes Birth Control

|

140

|

3

|

4.56

|

.73

|

.86

|

Brief Sexual Attitudes Communion

|

140

|

5

|

3.87

|

.85

|

.80

|

Brief Sexual Attitudes Instrumentality

|

140

|

5

|

3.01

|

.84

|

.75

|

Dyadic Sexual Desire

|

139

|

8

|

4.75

|

1.67

|

.90

|

Solitary Sexual Desire

|

139

|

6

|

2.37

|

2.04

|

.91

|

Sexual Sensation Seeking Scale

|

138

|

10

|

2.13

|

.58

|

.83

|

Hurlbert Inventory of Sexual Excitability

|

139

|

25

|

3.90

|

.63

|

.90

|

High K Strategy Scale

|

222

|

23

|

5.03

|

1.08

|

.96

|

Mini K

|

139

|

20

|

5.41

|

.67

|

.83

|

Future Orientation Subscale

|

139

|

5

|

3.79

|

.57

|

.64

|

Table 3

Life History Strategies Factor

Analysis Initial Communalities

Initial Communalities

|

|

High K Strategy

|

.40

|

Mini K

|

.31

|

Future Orientation Factor of CFC

|

.24

|

Brief Sexual Attitudes Permissiveness

|

.50

|

Brief Sexual Attitudes Birth Control

|

.15

|

Brief Sexual Attitudes Communion

|

.27

|

Brief Sexual Attitudes Instrumentality

|

.15

|

Sociosexuality

|

.51

|

Sexual Sensation Seeking

|

.34

|

Hurlbert Scale of Sexual Excitability

|

.33

|

Sexual Desire Inventory Solitary

|

.30

|

Sexual Desire Inventory Dyadic

|

.29

|

A Principal Axis

Factoring method of extraction with an Oblimin rotation was utilized. The

initial eigenvalues, 2.70 and 1.98 respectively, showed a clear two-factor

solution, with the first factor explaining 22.58% of the variance and the

second factor explaining 16.52% of the variance. Two other factors explained

11.92 and 9.35 percent of the variance, with 1.43 and 1.12 eigenvalues

respectively. Due to apparent “leveling off” as examined in the scree plot and

theoretical considerations, only the first two factors were analyzed further.

Both factors explained a total of 39.35% of the variance. There was little

difference between an Oblimin and Varimax rotation; the two factors correlated

at -.11.

The results of

the factor analysis confirmed the two-factor hypothesis; the factor-loading

matrix is presented in Table 4. The scales assessing sexual behaviors loaded

strongly on the first factor (e.g., .69 and .57) and subsequently loaded weakly

(e.g., .27) or negatively (e.g., -.03) on the second factor, with scales

assessing non-sexual behaviors; illustrating the distinct nature of these two

factors. Likewise, the scales assessing non-sexual behaviors loaded strongly on

the second factor (e.g., .57) and loaded negatively (e.g., -.15) on the first

factor; this reiterates the distinct and separate nature of these two factors. Contrary

to hypotheses, the Hurlbert Scale of Sexual Excitability loaded moderately on

the second factor, .46, and weakly on the first factor, .23, where it was

hypothesized to load strongest. Also, Brief Sexual Attitudes Instrumentality

loaded moderately on the first factor as predicted, .22, but also loaded

moderately and negatively on the second factor, -.33, not as predicted. Brief

Sexual Attitudes Birth Control loaded weakly on both factors, .05 for the first

and .28 for the second. Brief Sexual Attitudes Permissiveness cross-loaded, but

in the hypothesized direction: positively on the first factor, .56 and

negatively on the second factor, -.40. Brief Sexual Attitudes Communion loaded

weakly on the first and second factor, .17 and .01 respectively.

Table 4

Life History Strategies Factor

Matrix

Factor 1

|

Factor 2

|

|

High K Strategy

|

-.02

|

.52

|

Mini K

|

-.26

|

.57

|

Future Orientation Factor of CFC

|

-.15

|

.46

|

Brief Sexual Attitudes Permissiveness

|

.60

|

-.40

|

Brief Sexual Attitudes Birth Control

|

.05

|

.28

|

Brief Sexual Attitudes Communion

|

.17

|

.01

|

Brief Sexual Attitudes Instrumentality

|

.22

|

-.33

|

Sociosexuality

|

.51

|

-.38

|

Sexual Sensation Seeking

|

.69

|

.27

|

Hurlbert Scale of Sexual Excitability

|

.23

|

.46

|

Sexual Desire Inventory Solitary

|

.57

|

-.03

|

Sexual Desire Inventory Dyadic

|

.48

|

-.14

|

The factor labels

suited the hypothesized predictions; Factor 1 was labeled the “r Factor” and Factor

2 being labeled the “K factor.” However, when factor scores were computed to

use in subsequent hierarchical regression analyses, the scales that did not

follow in line with the theoretical framework were eliminated. The Hurlbert

Scale of Sexual Excitability, Brief Sexual Attitudes Birth Control, Brief

Sexual Attitudes Communion, and Brief Sexual Attitudes Instrumentality scales

were dropped from the subsequent factor analyses, due to the lack of

theoretical support and the presence of weak or cross loadings.

K and r Factor scores. To compute

factor scores, Principal Axis Factoring method of extraction with a Varimax rotation

with Kaiser Normalization was utilized. HKSS, Mini K, Brief Sexual Attitudes

Permissiveness, Sexual Desire Inventory Solitary, Sexual Desire Inventory

Dyadic, Sexual Sensation Seeking, Sociosexuality, and Future Orientation were

inputted into the analysis.

The factorability of the eight scales was examined using the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin

measure of sampling adequacy, which was above the recommended value of .6

(.65), and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant, χ2 (28)

= 172.80, p < .01. Examination of

the anti-image correlation matrix revealed correlations above .5, with the

exception of the HKSS (.49), supporting their inclusion in the analysis. With

the exception of Future Orientation, HKSS, Sexual Desire Inventory Solitary,

Mini K, and Sexual Sensation Seeking, the initial communalities were above .3. Variance

is accounted for by the two-factor solution was 52.78%. The rotated factor

matrix is presented in Table 5. Factor scores were created for each of the two

factors, based on the mean of the items, which had their primary loadings on

each factor. Higher scores on the r Factor indicated greater endorsement of

sexual behaviors and higher scores on the K Factor indicated greater

endorsement of non-sexual behaviors. Descriptive statistics are

presented in Table 6. The skewness and kurtosis were within the tolerable range

for assuming a normal distribution and examination of the histograms revealed

the distributions to look normal.

Table 5

Life History Strategies Factor

Scores Factor Matrix

r Factor

|

K Factor

|

|

High K Strategy

|

.62

|

|

Mini K

|

.60

|

|

Future Orientation Factor of CFC

|

.52

|

|

Brief Sexual Attitudes Permissiveness

|

.72

|

|

Sociosexuality

|

.66

|

|

Sexual Sensation Seeking

|

.58

|

|

Sexual Desire Inventory Solitary

|

.49

|

|

Sexual Desire Inventory Dyadic

|

.51

|

Note: Factor loadings < .40

are suppressed

Table 6

Descriptive Statistics for r

Factor and K Factor Scores (N = 99)

M

(SD)

|

Skewness

|

Kurtosis

|

|

r

Factor

|

.00053 (.87718)

|

.34

|

.44

|

K

Factor

|

.00146 (.81292)

|

.44

|

-.40

|

Effectiveness Score Factor Analysis

In order to test hypothesis one,

a factor analysis was ran to compute the participants’ contraceptive method

effectiveness score. First, Primary

Method Specific Errors, Primary Method General Errors, General Errors in

Contraceptive Use, and General Knowledge of Contraception was factor analyzed

and one factor was extracted using Principal Components Analysis. Examination

of initial communalities and the anti-image correlation matrix revealed General

Knowledge of Contraception did not correlate with the other three scales, and

was consequently dropped from analysis. The factorability of the three scales

was examined using the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy, which

was satisfactory (.53). Also, Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant, χ2 (3)

= 16.83, p < .01. A Principal

Components Analysis was utilized to extract one factor from the three scales,

and 44.72% of the variance was explained by this single factor. The component matrix

is presented in Table 7. Component scores were

created from the single factor solution; higher scores indicated higher general

and method specific use skills. In the next step, participant’s scores

on the General Knowledge of Contraception Scale were converted into z scores and subsequently averaged with

the contraceptive use skills factor scores. This represented a composite

effectiveness score of their contraceptive use skill and contraceptive

knowledge. Lastly, participants’ specific method was taken into account by

multiplying their composite score of use skills and knowledge by a percentage.

This percentage was derived from known contraceptive efficacy (see Trussell,

2007): with typical use, eight women (of 100) experience an unintended

pregnancy within the first year of use of the pill or ring, therefore

participants using either the pill or ring received 92% of their composite

effectiveness score. To calculate what percentage of their score they received,

pill and vaginal ring users’ composite scores were multiplied by .92, condom

users’ composite scores were multiplied by .85, and IUD users’ composite scores

were multiplied by .992. The resulting score was known as their overall

contraceptive effectiveness score. Descriptive statistics are presented in Table

8 and 9, separated by single method users and dual method users.

Table 7

Contraceptive Use Skill Factor

Analysis Factor Loadings for Effectiveness Score

Factor Loadings

|

|

General Contraception Use Skill

|

.72

|

Primary Method General Use Skill

|

.78

|

Primary Method Specific Use Skill

|

.47

|

Table 8

Descriptive

Statistics for Contraceptive Effectiveness Score, Single Users

M(SD)

|

Skewness

|

Kurtosis

|

|

Effectiveness

Score (skill)

|

-.24(.96)

|

-.67

|

.02

|

Effectiveness

Score (skill &

knowledge)

|

-.09(.80)

|

-.12

|

-.59

|

Effectiveness

Score (skill,

knowledge, & method)

|

-.09(.66)

|

-.28

|

-.42

|

Table 9

Descriptive

Statistics for Contraceptive Effectiveness Score, Dual Users

M(SD)

|

Skewness

|

Kurtosis

|

|

Effectiveness

Score (skill)

|

.49(.91)

|

-.85

|

.74

|

Effectiveness

Score (skill &

knowledge)

|

.22(.72)

|

-.60

|

1.48

|

Effectiveness

Score (skill,

knowledge, & method)

|

.26(.58)

|

.09

|

-.58

|

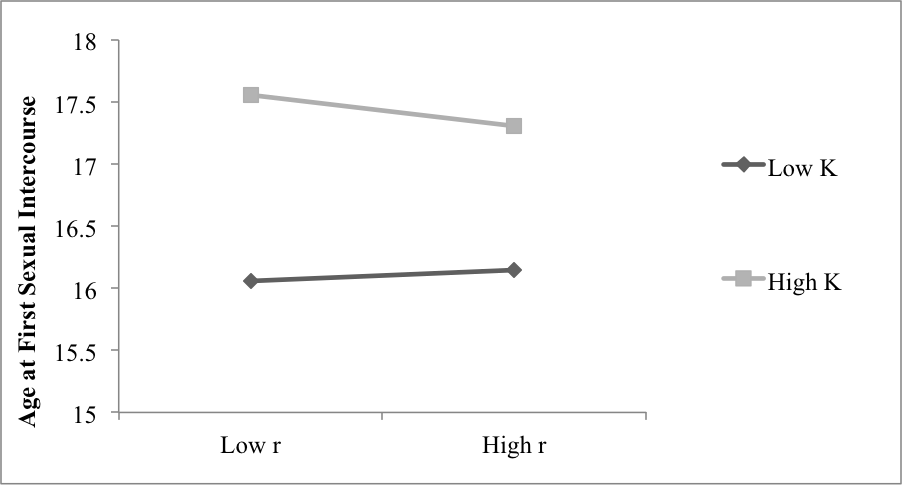

Results

Contraceptive Effectiveness

It was

hypothesized that an interaction between r and K strategies would be found to

predict contraceptive method

effectiveness, such that high r and high K women would utilize the most

effective methods. Results did not support my first hypothesis, N = 71. To examine the contribution of the

r Factor, the K Factor, and their interaction to explain contraceptive

effectiveness (skill only), a hierarchical multiple regression analysis was

performed. The r Factor was entered in the first step, the K Factor was entered

in the second step, and step three included the Interaction variable (r Factor

X K Factor). Before analysis was performed, the independent variables were

examined for collinearity. Results of the variance inflation factor (VIF) were

all less than 2.0, and collinearity tolerance were greater than .80, suggesting

the estimated βs were well established in the model. The

results were not significant, p >

.05.

Results from analysis on contraceptive effectiveness (skill

and knowledge) did not support my first hypothesis, N = 99. To examine the contribution of the r Factor, the K Factor,

and their interaction to explain contraceptive effectiveness (skill and

knowledge), a hierarchical multiple regression analysis was performed. The r

Factor was entered in the first step, the K Factor was entered in the second

step, and step three included the Interaction variable (r Factor X K Factor). Before

analysis was performed, the independent variables were examined for collinearity.

Results of the variance inflation factor (VIF) were all less than 2.0, and

collinearity tolerance were greater than .92, suggesting the estimated βs were well established in the model. The results were not

significant, p > .05.

Results from analysis on contraceptive effectiveness (skill,

knowledge, and method) did not support my first hypothesis, N = 76. To examine the contribution of

the r Factor, the K Factor, and their interaction to explain contraceptive

effectiveness (skill, knowledge, and method), a hierarchical multiple

regression analysis was performed. The r Factor was entered in the first step,

the K Factor was entered in the second step, and step three included the

Interaction variable (r Factor X K Factor). Before analysis was performed, the